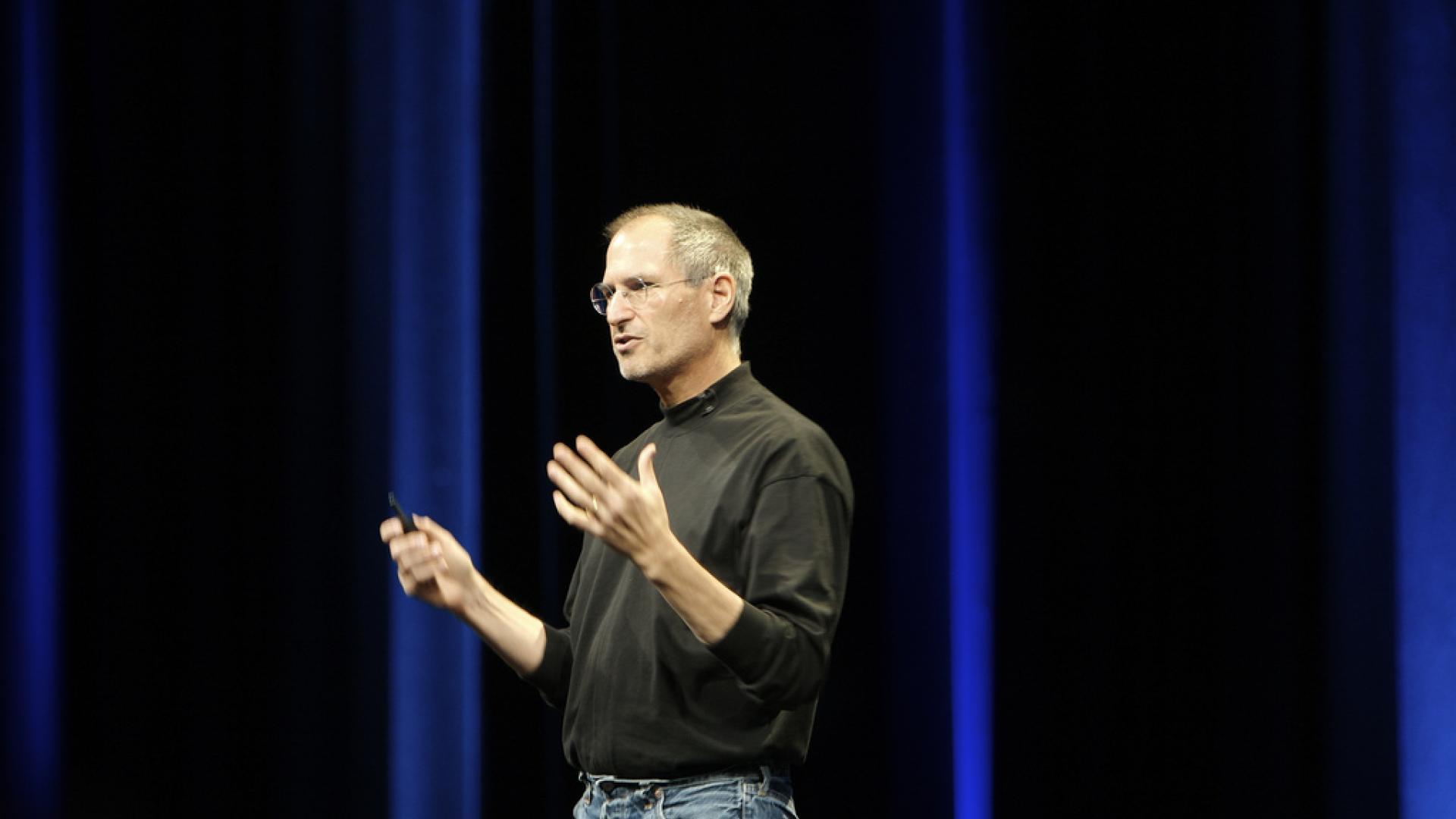

The death of Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple, in October was followed by an outpouring of collective grief around the world and eulogizing of Jobs’ contribution to the fields of business, design and technology.

Steven Levy, in his Wired Magazine obituary, wrote “[Jobs] was the most celebrated person in technology and business on the planet. No one will take issue with the official Apple statement that The world is immeasurably better because of Steve.”

Bill Gates of Microsoft responded to his peer’s passing: “For those of us lucky enough to get to work with Steve, it’s been an insanely great honor.”

And NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg wasn’t the only one to make the following comparison: “Tonight, America lost a genius who will be remembered with Edison and Einstein, and whose ideas will shape the world for generations to come.

But Jobs also had his detractors, and as noted in the New York Times it didn’t take long for people to come forward with their less positive evaluations of his contribution: “The Steve Jobs backlash began as quickly as the mythmaking had. Candlelight vigils were just starting to form outside Apple stores worldwide when bloggers began their assault. “Was Steve Jobs a Good Man, or an Evil Corporate CEO and Wall Street Shill?” asked a contributor on the Occupy Wall Street website.”

Interestingly some of the more vocal criticism of Jobs during his lifetime came from within the non-profit sector. In 2010 influential non-profit technology specialist Beth Kanter wrote a blogpost entitled “Why I’m Gonna Ditch My Iphone for Android,” arguing that Apple simply had no reason to prohibit donation apps on their popular smartphone. Indeed, Britain’s own Minister for Civil Society Nick Hurd wrote to the company asking them to explain – and change – this policy.

It perhaps goes without saying that all individuals, no matter how exceptional, have their strengths and their weaknesses, and perhaps Jobs’ clarity of vision and drive are both what made him so successful and what closed his company’s eyes to the needs of the voluntary sector (the ban on donation apps remains). But whether you’re a big Apple fan, or uncomfortable with the adulation poured on its visionary, I think the charity sector has some useful things to learn from Jobs.

1. The personal touch from your Chief Exec

Jobs was known for sometimes personally replying to emails sent to his work email address, and while his responses could be curt (“Nope” being just one example), this sense of being able to communicate directly with the person at the top was important to many Apple customers, and may have contributed to their renowned brand loyalty. Interestingly, this direct connection has been successfully used by other organisations – until recently the direct email address for the Chief Exec of Nationwide Building Society was readily accessible, and was a great way to show that the mutual organisation was connected to the members it claims to serve. Nationwide withdrew the email address recently after it was flooded with complaints because of changes to the Society’s current account, indicating what can go wrong if an organisation is seen to not really be listening.

So perhaps your Chief Exec can reply to some emails that come in from supporters, or take the time to personally thank a person who has regularly raised money through events for your cause (no matter how large or small the amount). This could be a great way to invigorate supporters, show them that their pounds really do matter and that the people at the top are listening.

2. Not doing things

Deciding what NOT to do can be as important as deciding what to do. When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in the mid-1990s after his earlier infamous ouster, he reduced the number of products Apple sold. Furthermore, I have always found it interesting that Apple hasn’t ever got into the market of all the additional kit you need when you buy a computer, or doesn’t offer multiple headphone options (all you get are those little white buds). No, they keep it simple and leave others to fill in some of the gaps. Perhaps charities need to put time into deciding what they are not doing, as well as working out their key areas of work. This is all the more true since we know that the general public worries about duplication in the charity sector. So, don’t be scared to acknowledge the fact that there are activities other organisations might be able to do better than you. And then focus on what you do best.

3. Tweaking, not just inventing

In his recent New Yorker article, Malcolm Gladwell argues that Jobs’ real genius lies in the fact that he was a “tweaker” rather than an inventor:

“In the eulogies that followed Jobs’ death, last month, he was repeatedly referred to as a large-scale visionary and inventor. But Isaacson’s biography suggests that he was much more of a tweaker. He borrowed the characteristic features of the Macintosh—the mouse and the icons on the screen—from the engineers at Xerox PARC, after his famous visit there, in 1979. The first portable digital music players came out in 1996. Apple introduced the iPod, in 2001, because Jobs looked at the existing music players on the market and concluded that they “truly sucked.” Smart phones started coming out in the nineteen-nineties. Jobs introduced the iPhone in 2007, more than a decade later, because, Isaacson writes, “he had noticed something odd about the cell phones on the market: They all stank, just like portable music players used to.”

So, don’t worry personally about being the one to make a breakthrough at work, or think that your organisation needs to discover a radical solution to a problem. Instead, look at what you and others are doing and ask, “How can we make what we are doing even better? How can we improve on the services already being provided to that group?” Rather than looking around for the next big thing, consider how some Jobsian tweaking could make a difference.

4. What every charity can learn from the Apple Store

One thing Jobs and Apple tweaked impressively was the retail experience. Walking into an Apple store is quite unlike walking into the electronics stores I remember as a kid. With loads of computers and gadgets to play around with, nobody hassling you about whether or not you want to buy something, and a big, airy space, Apple stores are a place in which people enjoy spending time.

And the way the stores are designed and managed is good for the bottom-line too – Apple has seen a 54 percent increase in its profit in 2011, a year not noted for positive economic results. More specifically Apple's stores earned $14 billion over the year ending in June 2011, “which allowed the company to top rankings of 20 US retail chains in terms of merchandise value sold per square foot of store,” according to the Apple Insider website.

And the training of Apple staff makes a particular contribution to this success. Apple Store employees receive extensive training before they are allowed to work on the shop floor, spending up to a few weeks shadowing colleagues before working solo. And a lot of emphasis is placed on the language that staff use – they’re encouraged to avoid phrases such as “unfortunately,” opting for more neutral phrases such as “it turns out” if they cannot help with something.

Thinking through the language used to communicate, and always being attentive about it – whether it’s with customers and potential customers, supporters and potential supporters, or service users – is something that businesses, charities and other organisations can all learn from Apple.

5. Seek mentorship; offer menteeship

An article in Forbes magazine about the lessons we can learn from Steve Jobs, focused on how he sought out mentors. Early on in his career he had the gumption to ask one of the co-founders of Intel to provide him with advice. And research has shown that it is those who have a mentor behind them, pushing or encouraging them, listening to them and providing them with advice that are among those most likely to succeed:

“When researchers look at the events in a person’s past that seem to make a difference in his or her success, they often find that somewhere, at some point, there was a person who believed in him or her, who cared, who took the time to listen and to sometimes give advice and information, contacts and relationships. Sometimes such people just told stories. And, seemingly most important, they gave the young person a sense of self worth and confidence in his or her ability to do something significant.”

And indeed in my own academic research in a completely different field – women in politics – it has been shown that one of the reasons women are less likely to become candidates for political office is that they don’t have people behind them suggesting they run or putting in a word for them with political parties in the same way that men with equal qualification for political roles do.

So, if you are starting out in the charity sector, take a look around you and ask yourself who might be able to provide advice on future steps. And if you are a more seasoned charity sector professional, are there new members of staff you could be encouraging and supporting? Because Steve Jobs calling up the heads of major Silicon Valley companies when he was a teenager obviously didn’t hurt.