Fiona Wallace looks at the re-emerging ‘sock puppets’ narrative and why the issue of has been blown out of proportion.

Our research with MPs shows that the top organisations impressing MPs are more financially independent than the charity sector average, suggesting that effective lobbying requires voluntary income. Every six months for the last 15 years, as part of nfpSynergy’s Charity Parliamentary Monitor, we have asked a representative sample of 150 MPs to spontaneously name the charities that have impressed them, and to give the reasons why.

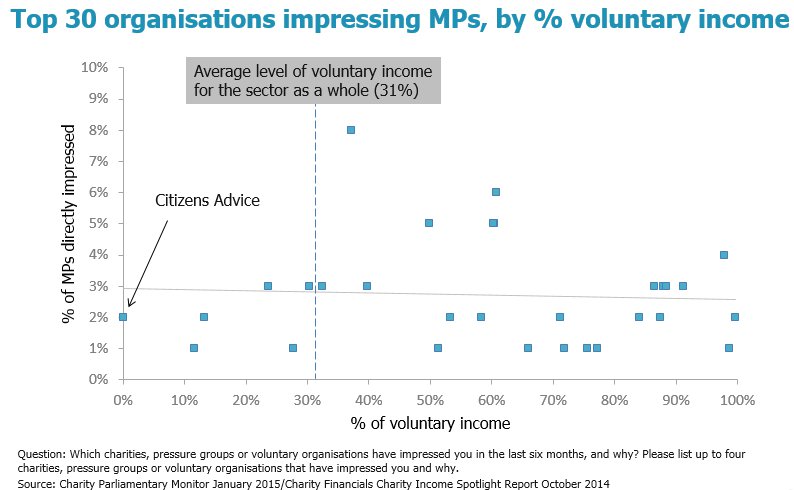

When we calculated charities’ average voluntary income as a percentage of total income, we found that the total mean average voluntary income for the top 30 UK charities impressing MPs in January this year is 60%, compared to the 31% sector-wide average.

70% (i.e. all but 9) of the top 30 have at least 50% voluntary income, and only 6 of the top 30 UK charities that MPs claim most impressed them in the last six months have less than the 31% sector-wide average percentage of voluntary income (as proportion of total income).

To add to this, whilst it’s true that absolute (as opposed to proportional) levels of voluntary income bear little correlation as such to impressing MPs, even those very few top 30 charities with below-average proportional voluntary income still seem to have significant absolute amounts of voluntary income, by brute virtue of their large size. The one exception to this would be Citizens Advice, who impressed 2% of MPs despite not having any voluntary income. However the reasons MPs were impressed with Citizens Advice were because of their local service provision and advice to MPs on how to help constituents, rather than their lobbying work.

Although the organisations that stand out in this measure generally change from each survey to the next, we see the same pattern every time we have asked MPs this question; that the organisations most impressing MPs have higher than the mean average level of voluntary income.

I think these findings add clarity to ongoing ‘sock puppet’ debates. Over the last few years, there has been a recurring debate between politicians, think tanks and the charity sector as to whether charities that receive statutory funding should be able to engage in political campaigning. In 2012 the Institute of Economic Affairs published a paper arguing that state-funded charities that are campaigning “…can create a ‘sock puppet’ version of civil society giving the illusion of grassroots support for new legislation.”

In February this year Eric Pickles, the communities secretary, adopted the ‘sock puppet’ narrative when adding a clause to his department’s grant agreements and advocating for other departments to do the same. With much condemnation from the sector, his clause said that payments could not be used to support any activity that seeks to influence parliament, government or political parties. Last month at the Conservative Party Conference, the debate re-emerged when the Institute of Economic Affairs hosted a fringe event to discuss whether the state should fund pressure groups, showing this is still a hot topic for the government.

Supporters of the ‘sock puppet’ narrative warn that we are at risk of creating a version of civil society where charities that are heavily state funded are the ones influencing change, which is undermining our democratic processes. What is missing from these debates is an account of who is actually being effective in lobbying MPs, rather than the focusing on who is technically lobbying government. When we focus on who is effectively influencing change with MPs it becomes clear that the worries of state-funded charity campaigning have been overstated, as consistently the charities that impress MPs are those with a significant level of voluntary income.

Voluntary funding gives charities a degree of independence from governmental, statutory sources, which is enabling them to be effective in their parliamentary campaigning. The supposed threat that organisations receiving a high degree of state funding are having a disproportionate level of parliamentary influence is not severe in the way that the government and think tanks are suggesting it is. I think the system is in fact self-balancing, as the charities impressing the most MPs are those with significant proportions of non-statutory income.

The Charity Parliamentary Monitor (CPM) is an effective and affordable way to regularly track how your organisation is perceived at Westminster. We survey a representative sample of MPs four times a year and 100 Peers annually. You can use the research to strengthen and evaluate your parliamentary campaigns, benchmark your organisation’s performance, identify ways to engage with politicians and understand how trends at Westminster will affect your charity. For more information about this research, download the briefing pack or contact Fiona Wallace at cpm@nfpsynergy.net.