I know. *Another* piece about the rise of meat-free diets. With the memory of that delicious, organic Christmas turkey you researched specially still fresh, this may not be the most appetizing topic. Indeed, scarcely a day went by last year without a related headline or opinion piece, and I realise that many will have had their fill of the latest hip, lifestyle ‘fad’. But the truth is, veganism has gone beyond vogue. 2018 was the year veganism went mainstream, with Greggs bringing out a vegan sausage roll and numerous vegan documentaries available to stream on Netflix, (the latter instrumental in turning my Dad, twin and girlfriend to plant-based diets).

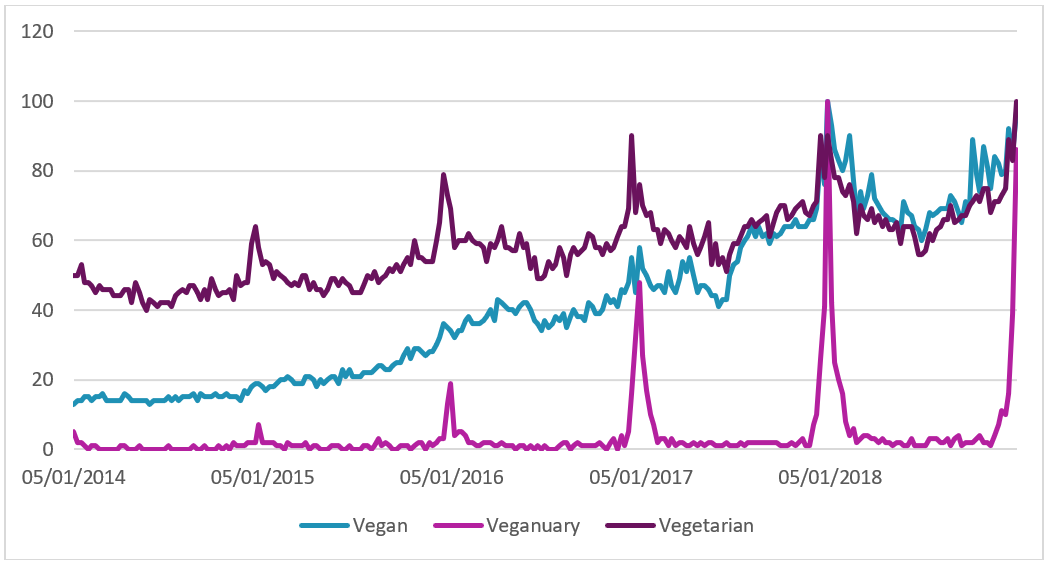

Estimates vary - one survey suggests there could be as many as 3.5 million vegans in the UK[1]- but this is clearly part of a longer trend. The Vegan Society have found that the number of vegans nearly doubled twice in the last four years: from 0.25% (150,000) in 2014, to 0.46% (276,000) in 2016 and reaching 1.16% in 2018 (600,000).[2] “Veganuary”, the campaign to promote veganism, is emblematic of this growth. Championed by the charity of the same name, it grew by a record 183% last year, with over 168,000 committing to try a vegan diet for a month.[3] The campaign appears to be effective, with a study showing that 62% of participants intended to stick to their new lifestyle choice[4]. It is important to note that the campaign’s impact does not appear to be limited to those trying out veganism, with general interest in meat-free diets consistently generated during this period (see below). Indeed, with record numbers expected to try Veganuary this month[5], Forbes has already christened 2019 the year of the vegan.

Figure 1: Google Trends chart for ‘Vegan’, ‘Veganuary’ and ‘Vegetarian’ over time, UK*

Google Trends, search terms and topics.

*Numbers represent search interest relative to the highest point on the chart for the given region and time. A value of 100 is the peak popularity for the term. A value of 50 means that the term is half as popular.

The burgeoning popularity of meat-free diets have come to wield an influence far beyond the niche, yoga-synonymous subculture it was once associated with. According to a Mintel report, as many as 56% of UK adults have eaten vegetarian/meat-free foods in the six months to July 2018- up from 50% in 2017- with younger Brits aged 25-34 (read Millennials) the most likely to have reduced meat consumption in the last year (40%).[6]

So- what has all this got to do with the price of meat (*sorry*), or the work of charities? Well, as the Economist put it, where millennials lead, businesses and Governments will follow.[7] Companies across the world are adapting to the fact that the meat-free market is a lucrative one. Sales of meat-free foods have grown 22% between 2013-18, with sales forecast to jump a further 44% by 2023 and reach £1.1bn.[8]

Charities are not immune from these changes - perhaps their exposure is more pronounced. After all, they are borne from wider society and in response to the causes it perceives as important. They therefore cannot afford to ignore the shifting habits of the population, especially when it touches on the moral and ethical issues which they are supposed to be leading proponents of. And as our own research has found, socially-conscious young people[9] are likely to be the volunteers of today (and the donors of tomorrow). Ignore at your peril.

Campaigning and diets- peas in a pod…

So, are charities grabbing their slice of the (meat-free) action? And if not, should they?

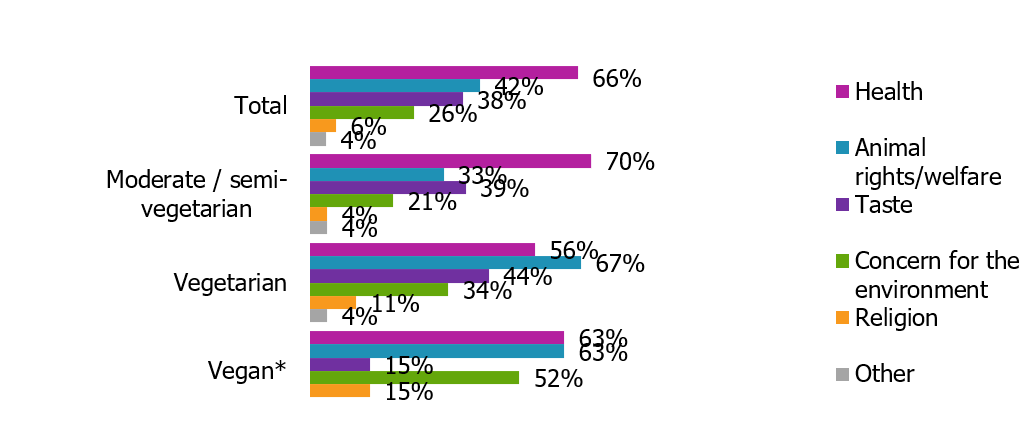

The first challenge in understanding the interplay between reduced-meat lifestyles and charities is to identify what motivates people to follow these diets. Our research indicates that health is the primary reason (two-thirds of the public), with animal rights/welfare ranking as the second highest motivation (42%). A quarter of people who chose these diets did so because of concerns for the environment.

When examining the reasons stated for each dietary choice, we can see below (Fig. 2) that while health is clearly the main motivating factor for semi-vegetarians, there is also evidence that vegans are more likely to have chosen this diet out of concern for the environment than either vegetarians or those following a moderately vegetarian diet (with a caveat on the small base size for the vegan group).

Figure 2: Reasons for vegetarian/vegan diet by dietary choices

“You indicated that you follow a vegetarian / partly vegetarian or vegan diet. Please choose as many reasons from the list below as apply to why you follow this diet.”

* Vegan group has a low base (27)

The public’s main reasons for following a reduced-meat diet tap into the key concerns of many charities, particularly those situated within working with health, animal rights/welfare and the environment. So, what is the third sector doing to engage this swelling potential supporter base?

Well, while quite a few environmental charities already claim the benefits of reducing animal product consumption on the environment (Greenpeace, Humane Society International, Eating Better campaign from Friends of the Earth, Meat Free Monday…), there are very few animal welfare charities highlighting the benefits of such diets on animal welfare (notwithstanding PETA and its Vegan Food Awards).

Health charities also appear reluctant to put a meat-free lifestyle at the centre of their campaigns, despite well-supported claims that it can help prevent or reduce a number of health issues (heart disease, diet-related cancers, type 2 diabetes).[10] Aside from Cancer Research UK’s Veg Pledge (a fundraising challenge to go veggie for November), the British Heart Foundation promotes a ‘balanced diet’ (“including some meat, fish, eggs”[11]) and has relatively little on the benefits of meat-free diets aside from recipe advice. Similarly, Diabetes UK offers guidelines for the suitability of a vegan diet for diabetics, while officially advocating a standard ‘balanced diet’ to prevent type 2 diabetes- despite the evidence[12][13] that a meat-free regime could be more effective. It would be facetious to expect charities to campaign solely on what, to many, is a demanding or unwelcome lifestyle change. But, at least in theory, it seems odd that so many charities do not at least also advocate a diet that appears to help realise their goals, whether health-related or otherwise.

...or recipe for disaster?

In practice however, the reasons for this reticence are complex, and worthy of consideration. Firstly, the science behind dietary health is loaded with confirmation bias and caveats, and merits caution. For example, the claims made in popular Netflix documentary “What the Health”, which inspired many thousands (including Lewis Hamilton) to ditch meat, has come under heavy criticism for exaggerating weak data[14] and misrepresenting scientific studies[15]. The BBC’s recent feature “Why cheese is no longer my friend” illustrates this well: investigating the disadvantages of milk and dairy, Tim Samuels asks three leading nutrition experts their opinions, and receives three different responses varying from tolerating daily consumption to reserving it for special occasions. As Samuels puts it, the lack of definitive answers on nutrition is bewildering. It is worth noting that even when the scientific footing is sounder, campaigning on sensitive personal issues such as diet and weight can be tricky- as Cancer Research UK found in the response to their anti-obesity drive.

Secondly, many charities choose to keep their distance for reasons of inclusivity. The RSPCA, for example, take the view that they must campaign for the “highest possible standards of animal welfare in all areas”[16]. In recognition of the fact that the majority of the general public eat animal products, one of their key aims is to raise awareness of the welfare of farm animals, rather than calling for the abstinence of eating animals altogether. In this sense, there is an instrumental purpose for animal welfare charities seldom campaigning for plant-based or reduced-meat diets as a means to fulfil their aims, due to its apparently limited power of persuasion[17].

Greenpeace provide an interesting case study of how charity engagement in meat-free diets can be complicated by both concern for consensus building and the perceived partisanship associated with vociferous advocates of veganism. The environmental organisation was criticised by sustainability-focussed documentary “Cowspiracy” (yes, it’s on Netflix), and their non-participation implied as a result of pressure from the meat industry. In a lengthy response, Greenpeace underlined their commitment to campaigning on the environmental impact of animal agriculture. Further, it stated that while they promote meat-free diets as a way to help the planet, they do not solely advocate veganism: “The ability to create change needs to be accessible to all, and work in a global context that incorporates cultural, class and accessibility issues.”[18] It can make sense, then, for charities to avoid centralising diet too heavily for risk of marginalising existing and potential supporters, and ignoring areas of concern that require implicit tolerance of animal slaughter or ‘exploitation’.

Food for thought

The question is- does this volatility mean that only stock speculators[19] can ride the so-called vegan wave?

There clearly remains huge potential. For example, a possible crossover reconciling concern for animal welfare and the environment may yet yield significant results. We carried out a particular statistical analysis (Principal Component Analysis) on last year’s data, to reveal some underlying patterns and relationships. We found that, when asking people what categories their favourite charities fall into; animal and environment sectors are more likely to sit together for a significant proportion of the population.

Does this open up a space for animal charities, and those working in the environment sector, to work together towards a dual aim of animal welfare and environmental benefit? As discussed, Veganuary has been effective in this space, with its message ‘Reduce the suffering of billions of animals. Help the planet’ successful in attracting adherents to a plant-based diet and raising awareness of environmental/animal welfare issues more broadly. It certainly seems that campaigning for plant-based and reduced-meat diets could help a swathe of charities both realise their goals and tap into a growing potential supporter base. Equally, they must be cautious not to alienate existing supporters, or neglect other areas in which they can make a difference. What is clear is that plant-based diets are here to stay, and however charities choose to acknowledge it, they should do so with both optimism and sensitivity.

*Full disclosure: I am a life-long vegetarian, with suspicions over dairy (but a complicated relationship with cheese). I am not a shill for Netflix.