Labour recently announced their intention to include a pilot version of Universal Basic Income in their next election manifesto. They are by no means alone in toying with this radical social policy. The idea has been championed by the Green Party and the SNP, as well as various pressure groups. With countries such as Finland, Spain and the Netherlands running pilot schemes, the implementation of Universal Basic Income is increasingly looking like a realistic possibility.

Figure 1: Swiss UBI activists during a public performance, Bern 2013

Universal Basic Income (UBI) is an unconditional flat-rate payment to all citizens. The payment is enough to cover the cost of living and thus provide basic financial security to all. Many politicians argue that this would be an effective way to release people from the “poverty trap” and promote social equality; others see it as a welcome way to cut the bureaucracy of the traditional means-tested welfare system.

The potential impact of UBI on society has been discussed for decades. Its early defender, the Australian journalist Lloyd Thomas, argued in the 1940s that the introduction of universal basic income would eliminate the need for charities.[1] Few people would share this belief today. However, the impact of UBI on the non-profit sector would certainly be significant. What could charities expect from it and should they join the ranks of its supporters?

To help me answer this question, I spoke to Amira Jehia, the co-founder of a prominent German initiative Mein Grundeinkommen that campaigns for UBI. Amira has a wealth of experience in experimenting with UBI as well as working in the non-profit sector.

Preventing precarity

Like many other sectors, the non-profit sector has been affected by the recent rise of precarious, ‘flexible’ labour. The proportion of UK non-profit sector workers on full time contracts is currently 63%, which is lower than in both the public (70%) and private (75%) sectors.[2] Precarious working conditions are a notorious source of much stress and worker burnout. Recent research revealed that given the special reliance of the non-profit sector on the on people, having a workface that is precariously employed impacts the organisational structure of charities as well as their ability to help vulnerable communities.[3]

UBI may offer a remedy. It may be able to provide necessary support to those who have passion for helping yet who get put off by the insecure environment of the non-profit sector.

“I see a lot of great ideas on how to solve many social problems, such as childcare or other care work, when talking to people who are passionate about these subjects. However, few people are ready to give up a well-paid job or simply one that pays their bills to try something different with no safety net. UBI is a safety net. And the people who need and deserve that the most are those who seek to improve the lives of others.”

Amira Jehia

According to this view, UBI would give people more space to experiment and thus benefit the non-profit sector immensely.

This is also true of volunteering. nfpSynergy research reveals that the appetite for volunteering amongst young people has been steadily growing over the years,[4] with the desire to help their communities being the strongest motivator. However, the financial pressure to hold on to paid jobs often stands in their way. Not having enough time due to changing home/work circumstances is the top reason for people to quit volunteering.[5] Moreover, when asked which factors would make people consider volunteering in the future, people named the possibility of volunteering without a specific time commitment as the most important factor.[6]

Figure 2: “The world’s biggest poster with the world’s biggest question”, Geneva 2016

The introduction of UBI would make it much easier for people to spend a proportion of their time volunteering. “Since all people would have their basic needs covered, they wouldn’t be as dependent on salary anymore,” says Jehia. “It would give people the chance to follow their passion.” The testimonials of participants in the Finnish UBI experiment seem to corroborate her view.[7]

From basic needs to basic welfare

Social issues are by far the largest focus of the UK non-profit sector, both in terms of spending and in terms of the number of charities working in the field.[8] For example, the number of organizations dedicated to social service provision are five times larger than the number dedicated to health. The concern about social issues amongst the British public is also substantial.

The introduction of UBI could help people get out of poverty. In this way, it may end many social problems that Britain is facing due to rising inequalities and government austerity measures. It is not hard to see how this could alleviate a certain burden placed on charities.

An example of how this could work is provided by food banks. Trussell Trust currently runs more than 2,000 food banks across the UK.[9] Their usage of has reached its historical record in 2018, with Trussell Trust food banks delivering over a million three-day emergency food supplies to people in crisis over the period of one year. With everyone provided with the essential means to live, they will no longer need to be turning to food banks to help them figure out what their next meal will be. UBI could also reduce the need for homeless shelters, clothes banks and similar provisions.

Another way in which UBI could reduce charities’ workload is through reducing the bureaucracy associated with applying for social benefits, proving that one is looking for a job, etc. This aspect of UBI has been emphasised by economists such as Milton Freedman. In the UK there are currently many charities provide guidance and advice on how to navigate the social benefit system. These include Advice UK, Law for Life and Independent Age, to name just a few. By eliminating means testing, UBI would make the work of these charities easier.

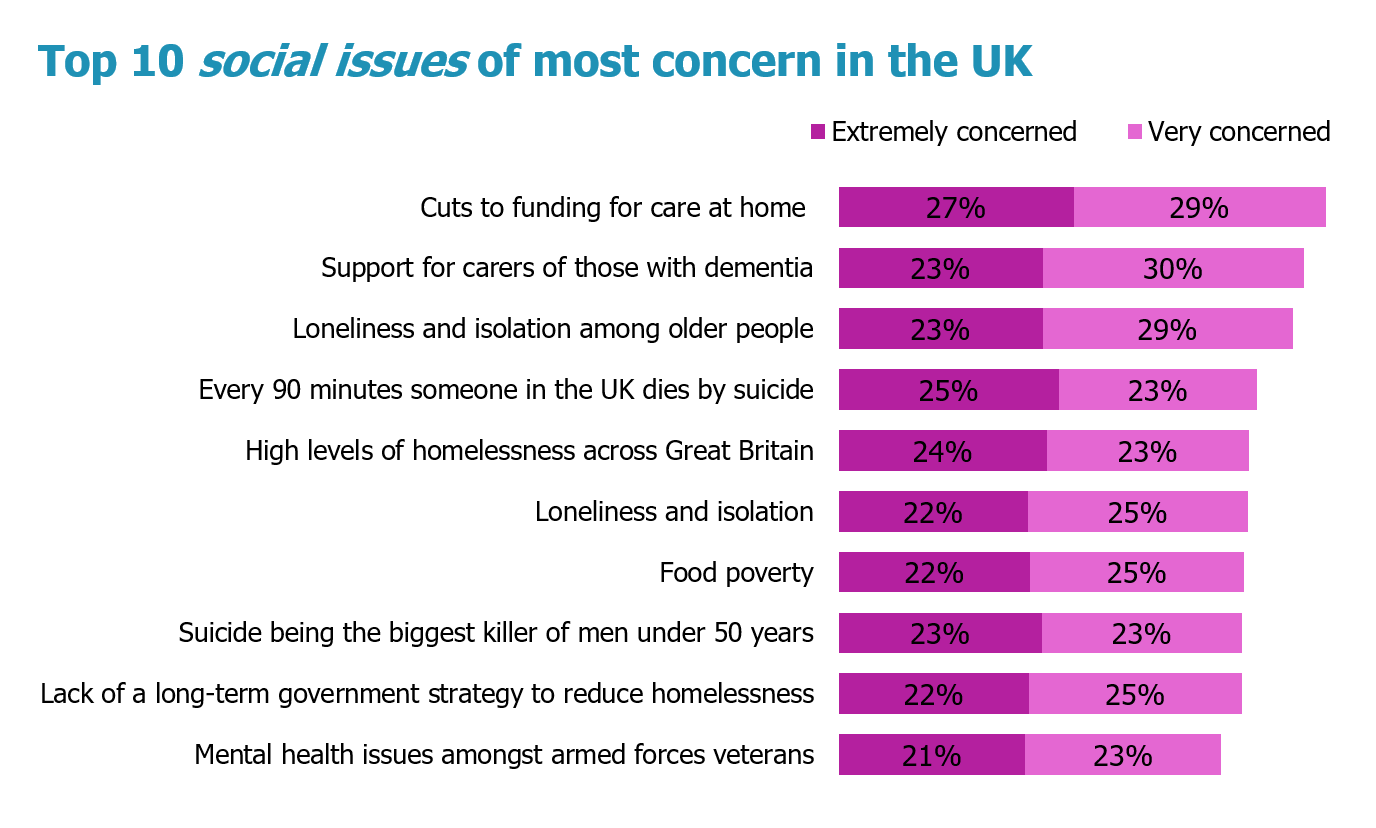

Figure 3: Top 10 social issues of most concern in the UK

“Thinking about the following social issues, please state how concerned you are about them?”

Source: Charity Awareness Monitor, October 18, nfpSynergy | Base: 1,000 adults 16+, Britain

However, Jehia is right to point out that “UBI ain’t a solution to every problem”. In fact, she thinks that the need for the non-profit sector would hardly decrease with the introduction of UBI. Our research supports this view. When we look at the 10 social issues that the British public is most concerned about, only 4 of them are directly related to poverty. These include cuts for care services, food poverty and homelessness (see figure 3). On the other hand, the majority of worrisome social issues are much more complicated, relating to suicide, loneliness and isolation amongst old people, and mental health.[10] It goes without saying that many charities work on issues completely unrelated to social welfare.

Although money could certainly help, solving these issues would require a much deeper social intervention than merely giving people basic income. Perhaps the safest thing to conclude is that instead of eliminating the need for non-profit sector, UBI would enable charities to advance more nuanced methods of welfare provision. In particular, it would enable charities to shift their focus from providing basic goods to providing personal care. Charities would be able to make the most out of their human capital, which many people regard as their “greatest strength.”[11]

Time to experiment

To sum up, the non-profit sector is likely to benefit rather than suffer from the introduction of UBI. First, UBI would empower individuals by giving them more independence. This would make it easier for people to both work and volunteer for non-profit causes they believe in. Second, it would alleviate some of the workload of social welfare charities, enabling them to focus their attention on issues where complex human intervention is required.

Amira Jehia has no doubts that charities should endorse UBI as a policy. I asked her what should charities sympathetic to the idea of UBI do to help the cause, beside campaigning or lobbying:

“A great start to working on UBI could be to consider paying one to oneself. We have experimented with different systems and it was a strong motivator for our own staff to have a UBI that covers their needs even after working for our NGO. There are hundreds of ways to implement it on a small scale and the experiences from that would make a campaign even more credible.”

Amira Jehia

Perhaps we need more charities to follow Mein Grundeinkommen in running their own local UBI experiments?

[1] Thomas, Lloyd (1942), Basic Income for Social Security, Perth, W.A. : Organisation for Reconstruction

[2] UK Civil Society Almanac (2017)

[3] Baines et al (2014), Not profiting from precarity: The work of non-profit service delivery and the creation of precariousness, Just Labour: A Canadian Journal of Work and Society 22

[4] Generational divide in public attitudes towards volunteering, CAMEO, December 2017

[5] UK Civil Society Almanac (2016)

[6] Generational divide in public attitudes towards volunteering, CAMEO, December 2017

[7] Muraja, T. (2018), Universal basic income hasn’t made me rich. But my life is more enriching, The Guardian, available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/aug/07/universal-basic-income-rich-finland-work-benefits

[8] UK Civil Society Almanac (2018)

[9] Independent Food Aid Network (2017), http://www.foodaidnetwork.org.uk/

[10] Charity Awareness Monitor, October 2018

[11] McMullen, K. and Brisbois, R. (2003), Coping with Change: Human Resource Management in Canada’s Non-profit Sector, Ottawa: Canadian Policy Research Networks 4