Parliament returned from the summer recess this week and already the Prime minister has announced plans to reform the social care sector. Although it has been met with cross-party criticism (though increasingly muted from Conservative backbenchers), it signals a welcome break from the political neglect of what is a huge problem.

Johnson has publicly justified breaking his manifesto pledge that he would not raise taxes by suggesting that the policy comes in response to the pandemic. The stresses and strains of Covid-19 on the sector have been only too visible and the proposed £12bn investment represents an important long-term reform on the back of this.

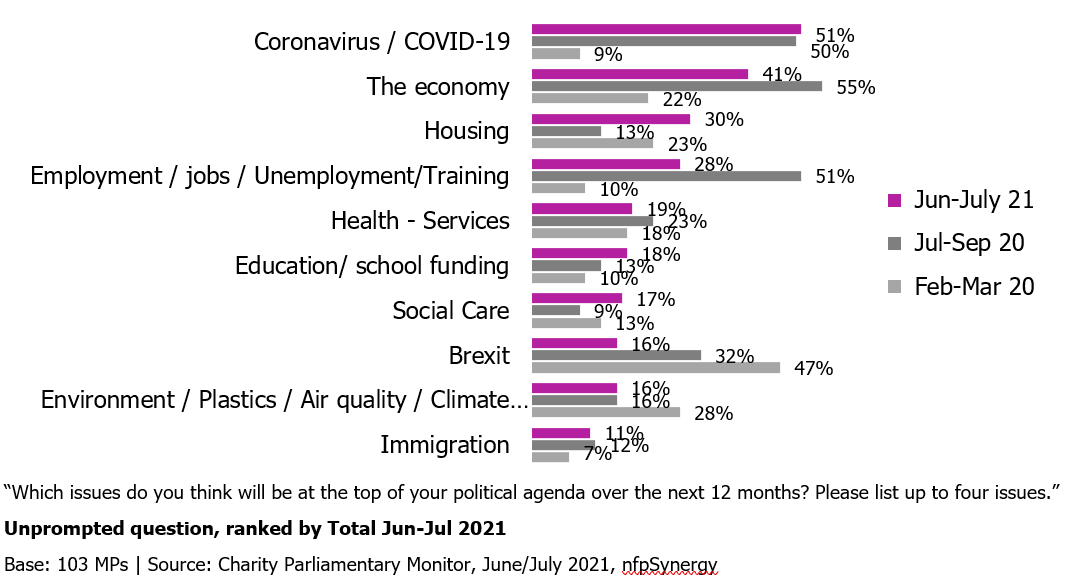

With the success of the vaccine roll-out and the decline of Covid-19 as an immediate national health threat, the plans suggest political space is being afforded to begin considering longer-term structural reforms. We canvased the opinions of 100 MPs in summer 2021 to see what their political priorities would be over the coming 12 months and how they have changed since summer 2020.

The pandemic is still the main concern for MPs

Covid is still the biggest concern for MPs, with 51% listing it as their main priority over the coming twelve months. Interestingly, however, both employment/jobs and the economy are no longer seen as such major political priorities.

Chart One: Issues at the top of MPs’ agenda

As Chart 1 shows, the percentage of MPs listing the economy as a ‘top of agenda’ issue rose from 22% pre-pandemic to 55% in July-Sept 2020. Similarly, employment/jobs rose from 10% to 51%. This was no doubt due to the significant pressure placed on the immediate and long-term health of both these areas during the first lockdown.

The latest round of data shows that employment/jobs has now dropped down to 28% and the economy to 41%. The vaccine roll-out has eased the stranglehold which the pandemic had on the economy and employment. Now, the question is which issues will benefit from the space this affords in the political agenda?

Social Care is still not a top priority for MPs

Although it is widely agreed that social care is in need of reform, the sector has often suffered from a lack of concrete political engagement. The omission of any social care reform plan from the Queen’s Speech in May this year was another example of this, especially given Johnson’s 2019 manifesto pledge to “fix the crisis in social care once and for all”.[1]

In our latest wave of research with MPs, although social care rose slightly from 9% to 17%, we cannot describe this as a ‘significant result’, meaning once again there has been no advance of social care as a political priority.

Social care suffers from the combined problem that it is an area that affects a minority of the population – predominantly the older demographic - coupled with the fact that it is an expensive problem to solve. Although Conservatives have now voted in favour of Johnson’s reforms, the opposition the Prime Minister has faced along the way shows how difficult it is to gain support on an issue that isn't a priority for MPs.

One Conservative backbencher commenting on the reforms said, “People have been through enough, and we should focus on getting the economy going again. Yes, social care is a ticking timebomb, but does it have to be right now? (…) It just doesn’t feel very Conservative, especially given the manifesto pledge.”

This comment goes to the heart of the social care crisis. The proposed reforms will be welcomed by the sector. However, the Prime Minister has faced a significant political bulwark from a party uncomfortable supporting a costly plan to address an issue that fails to register as a commonplace constituent concern - especially through something as ‘unconservative’ as raising tax. Whilst social care is widely recognised to be a ‘ticking time bomb’, whether there is the motivation to invest the necessary fiscal and political capital to address the issue is another matter.

Housing has resurfaced as a parliamentary priority

Conversations around housing have been a relatively consistent feature of public life over the last few years. The cladding crisis that followed the Grenfell Tower disaster highlighted the deadly inequalities in housing provision, and this has been just one part of a growing case to produce more affordable and more readily available housing.

And yet by summer 2020, ‘housing related issues’ had slipped down the political agenda with just 13% of MPs listing it compared to 23% prior to the pandemic. This likely reflects the immediacy of the Covid-19 crisis, as areas like jobs, the economy, and Covid itself took primacy over longer term social planning.

Housing has resurfaced however, with roughly 1 in 3 MPs (30%) listing it as a priority over the coming twelve months. This will no doubt result in part from the political space afforded by the vaccine roll-out to consider more longer-term issues. It is also likely that this resurgence will come directly from the pandemic itself, with the spotlight it has shone on the inadequacies and inconsistencies across the housing sector.

If the string of lockdowns has highlighted anything, it is the inequalities in space and living conditions. Newham, a borough of East London, has the highest levels of overcrowding across the country (with over 25% of the population affected) and suffered one of the highest Covid-19 mortality rates in May 2020, with 144.3 per 100,000 people dying.[2] As the rhetoric around Covid-19 as a ‘universal leveller’ has been debunked, the case for decent, affordable housing has been on the rise.

The green agenda is not re-building momentum with MPs

The summer of 2021 will likely be remembered by some as the year in which regions from Siberia to Sicily were ablaze. It will also be remembered as the summer where the IPCC predicted impending climate catastrophe unless radical political action was taken.[3]

The UK parliament is, however, yet to reflect the urgency of the situation. Environmental concerns and climate change have not increased as a priority – the percentage of MPs listing this as a top of agenda issue remains at 16%, down from 28% prior to the pandemic. Given that most protest and mobilisation efforts have had to cease, and the existential (or not quite so existential) threat of climate change has been replaced by the very immediate menace of the pandemic, it is perhaps unsurprising that the green agenda has slipped from the political radar.

Explanations in mind, these findings are no more palatable. The case for widespread climate action has never been more pressing, and what’s more, the global community has shown just how readily it can mobilise around a crisis given sufficient political motivation. The reaction to the pandemic saw militant state intervention, global medical collaboration, and the dramatic financialisation of vaccine production and distribution. All this points to a very real willingness to break from the prevailing politico-economic orthodoxy that governs the global community, given a sufficient mandate.

Ultimately, this just serves to underline the nature of the climate crisis as a crisis of political will. With COP26 on the horizon there will be mounting pressure on governments to move away from public statements of vague intent towards legally binding targets. If history is anything to go by, I wouldn’t hold your breath.