Naomi Croft

Two weeks ago I joined a Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) webinar discussing their UK Poverty 2023 report and the cost-of-living crisis. JRF highlight that an increasing proportion of the population across the UK are meeting their definition of poverty which is ‘when your resources are well below your minimum needs’. A staggering 13.4 million people are in poverty in the UK and the cost-of-living crisis is only making it worse . Increases in housing, heating and food costs mean more people will be able to meet their minimum needs.

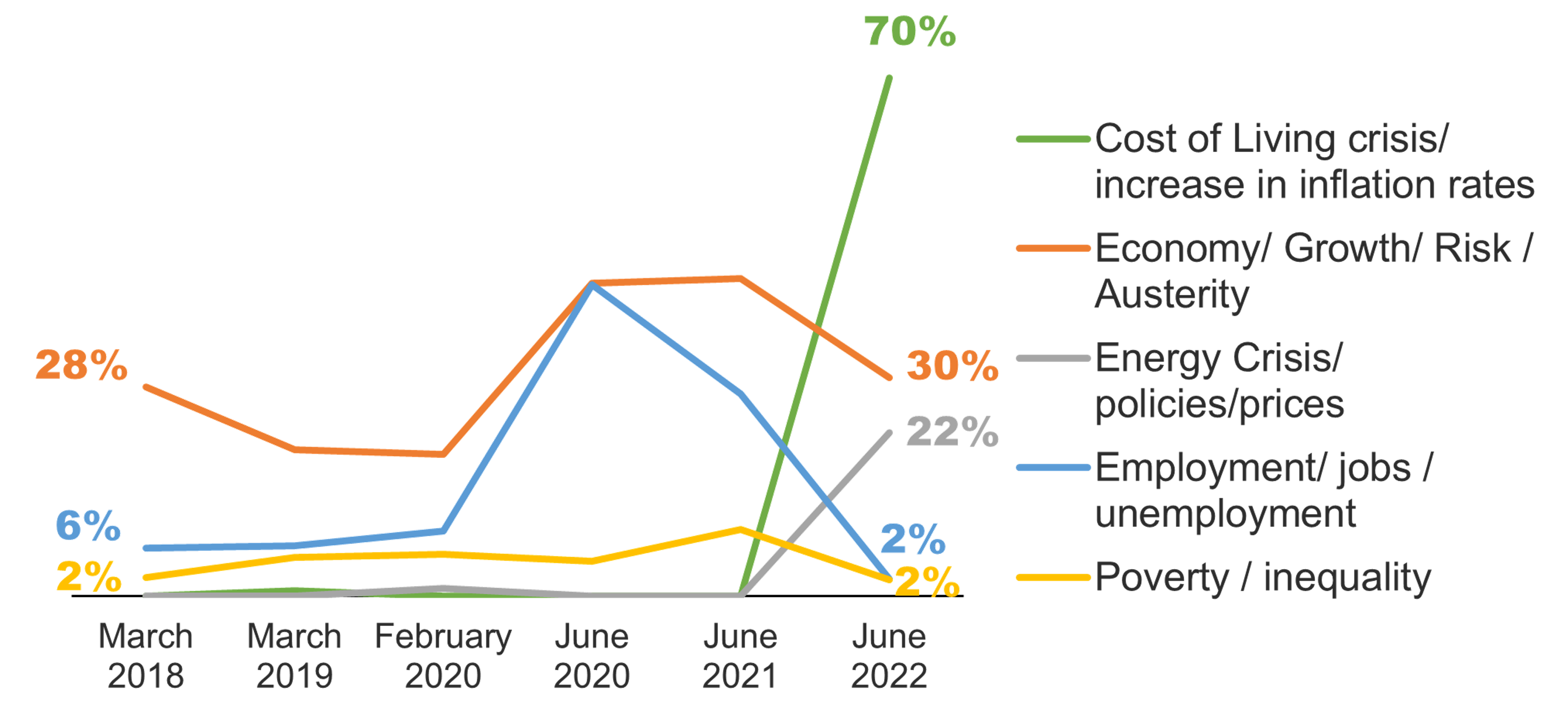

This got us thinking about the definition of poverty, its alignment with the cost of living crisis and how it is viewed by the general population, the charity sector and MPs. Our recent research with MPs showed that the cost-of-living crisis is a key issue for 70% of MPs. The crisis is dominating the agenda of the majority of parliamentarians for the 12 months from June 2022; MPs are clear these are the top issues for them to work on.

Chart: Issues expected at top of MPs’ agendas

“Which issues do you think will be at the top of your political agenda over the next 12 months? Please list up to four issues.” Unprompted question

Source: Charity Parliamentary Monitor, Mar 18 - Jun 21, nfpResearch | Base: 100 MPs

Despite this, only 2% of MPs said ‘poverty or inequality’ was a top issue. Why is the rising cost-of-living recognised by 70% of MPs as the urgent issue that it is, but ‘poverty’ has stayed at a 2% level since 2018? Does it matter that MPs don’t think poverty is a top issue?

It's important to consider the implications of language in this context. Is there a reason few MPs named ‘poverty’ as an issue? As was clarified by JRF the cost of living and poverty are intimately intertwined. Perhaps for some MPs ‘cost-of-living’ is shorthand for poverty. A constituent might go to their MP or a charity and say they can’t afford heating or food but might not say they are ‘living in poverty’.

This is something for not-for-profits to consider in their communications. In some of our other research we have seen that ‘poverty’ is not necessarily a useful descriptor as people don’t associate themselves with the word. The reluctance of MPs to recognise poverty is even more complicated and is perhaps reflective of the politically divisive nature of British socio-economic issues. With so many more people meeting the definition of poverty as a result of the cost of living crisis, charitable organisations are needing to adapt their language to appeal to both their service users and politicians in their efforts to combat the damaging effects of the crisis.

The future is also uncertain. With no end in sight for the ‘crisis’ and with the potential for these sky high costs of living to become normalised, what happens to all those extra people who have been pushed into poverty? Lack of political willingness to accept ‘poverty’ as a problem alongside the public’s aversion to the word probably means that it is not crucial for ‘poverty’ to be used as long as the cost of living issue stays top of mind. But long-term does this mean we miss having an overarching narrative of all the issues that feed into inequality? Scrutinizing the reasons behind this lingual conflict could be extremely important in understanding perceptions of poverty and therefore how to combat it best, particularly for the charities who are working to do this.

If you'd like to know more about our research with MPs, consider downloading a briefing pack below.