Anna Wates explores polling techniques, and why prediction can sometimes be a fool’s game

Votes are being cast by Labour members, affiliates and sign-ups all around the country in what appears to be quite an interesting leadership election after all. The polls have shown Jeremy Corbyn in the lead, ahead of competitors Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper and Liz Kendall. This at first seemed to come as a surprise – not least to the veteran left-winger himself – but now with just a week to go until results are announced on 12th September, the Corbyn campaign has gathered remarkable momentum. Yet with the polls having gone awry in this year’s general election, can we trust them?

At nfpSynergy, we regularly survey public opinion through tracking research and bespoke projects, helping charities anticipate and plan for the future. From our vantage point as market researchers, we thought we’d examine more closely the pitfalls of polling.

To start with a classic example: during the 1936 U.S. presidential election, general interest magazine Literary Digest ran a poll in its October issue. It sent ballots to one fourth of the nation’s voters, asking them which candidate they intended to vote for. The magazine received 2,000,000 cards in return, and, with such a large sample, confidently issued its prediction: Republican presidential candidate Alfred Landon would be the overwhelming winner, with 57% of the popular vote. As it turned out, Landon's actual electoral vote total was among record lows for a party nominee! The fault was entirely on the magazine’s polling techniques – the fact that its mailing list comprised its own readers, a group occupying a particular socio-economic position and more likely to vote for a Republican candidate. It’s what we as researchers would call non-probability sampling, when the sample tends not to be representative of the population about which it is attempting to speculate.

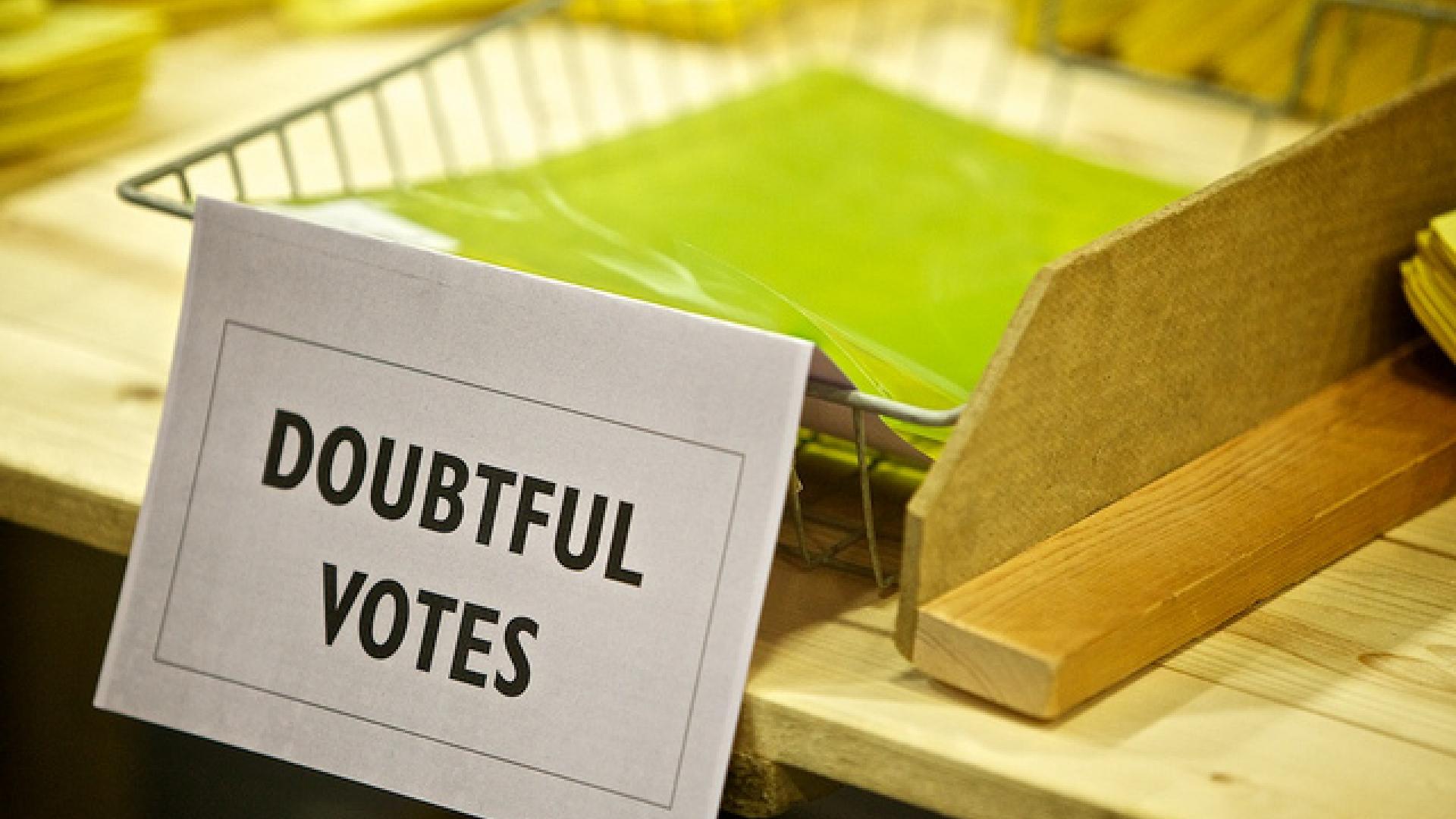

Despite the many caveats researchers might apply, polls nonetheless exert huge influence on political discourse. When the numbers came out putting Corbyn ahead last month, the ensuing political carnage has been brutal, with several Labour MPs threatening an apocalyptic split. The shock continues to reverberate around Westminster, evidenced by the disqualification of those recently signed-up members and affiliates who the party believes do not share Labour values.

In an earlier blog, we analysed the issues which emerged after this May’s general election, when pollsters drastically misjudged the gap between Conservatives and Labour. Many explanations have been offered – from lazy Labour voters who just didn't turn up on the day, or shy Tories unwilling to speak openly about voting for 'the nasty party', to the idea of late swing – that public opinion turned at the last minute. Perhaps most compelling is the impact of differential turnout and marginal seats, something difficult to capture at scale. Yet pre-election polls did get some things right, such as plummeting support for the Liberal Democrats, and the Ukip and Green shares of the vote.

Attempting to gauge an internal party election is even more complex, however, particularly when there’s little to anchor the results. You could attempt to weight the data reflecting votes cast five years ago, re-assigning Ed and David Milibands’ supporters to those candidates seen as the most logical fit, but this would be a very imprecise manoeuvre. Given the different conditions under which people are voting this time around (one member one vote), weighting the data according to past vote recall doesn’t feel comparable.

The absolute most important thing with polling will always be about getting the right sample – finding a representative proportion of women and men, accounting for region, and so on – as the Literary Digest example proves. This is standard practice for us at nfpSynergy. For our Charity Parliamentary Monitor, for example, we survey 150 MPs four times a year and 100 peers annually, taking care to keep our samples representative of the composition of Parliament, both for political party and region.

Ultimately, we might do well to treat the poll results as what they are: a situation report rather than prediction. They can tell you how much people know about the candidates, however, and this – taken together with the response to candidates’ campaigns and general noise on social media - can function as a barometer of sorts.