We need to add a new C-word to the burgeoning taboo lexicon. No, not a health condition. Nope, not Christmas either, as my colleague punned in her excellent blog about festive fundraising (read it here). I mean a real c-word. A topic or word so controversial it cannot even be referred to by name. It can provoke strained smiles, and a scramble to seize fresh territory for conversation. Or, it has the capacity to spark such strength of feeling that, like a faulty firework (or stick of dynamite), while its light might be bright, you will probably be burned in the process. Like Religion, Voldemort, VAR or the ending to the Sopranos (Tony’s still alive to me goddamnit!). Add to that list- celebrities. Specifically; celebrity endorsements of charities and/or charitable causes.

This was demonstrated most recently - and infamously- when David Lammy tweeted “the world doesn’t need any more white saviours” in response to a picture of Stacey Dooley with a child in Uganda as part of a film for the then upcoming Comic Relief. Of course, Overseas aid campaigning has a particularly troubled history - an entire awards category (the ‘Rusty Radiators’) is dedicated to challenging stereotypical portrayals of poverty and development. Certainly, this debate goes beyond celebrities; an examination of how lazily recycled tropes depicting African helplessness perpetuates eurocentrism is sorely needed[1]. Nonetheless, celebrity appearances do seem to serve as a lightning rod for (not unjustified) criticism - be it Stacey Dooley, Tom Hardy, Ed Sheeran, or Angelina Jolie. Perhaps they simply provide the most visible symptom of the underlying problems afflicting international development campaigns.

But scepticism towards the value of celebrity endorsements is not limited to any single cause, it is being questioned throughout the entire sector. Indeed, one Guardian journalist was moved to write an article calling celebrity endorsements “the curse of good causes”[2]. Why the criticism? And is charity engagement with celebs still justified?

There are many reasons to be suspicious of mixing celebrity with charity. Afterall, many associate celebrity culture with self-interest, insincerity and vanity. Or, as Tanya Gold put it in the same article, “a dystopia seething with hypocrisy and soaked with vanity.”[3] Certainly, there is cause to question the intentions of some celebrities - who does their charitable activity really benefit? As Daniel Drezner notes, campaigning on humanitarian causes helps stars like Angelina Jolie and Matt Damon access new, more serious outlets like political talk shows, or international conferences[4]. Is celebrities’ philanthropic work simply a way to add moral depth and polish to their image, simply an extension of personal brand development[5]? And if celebrities’ charitable activity is inherently narcissistic and shallow, does this also taint the cause to which they lend their endorsement?

It is not hard to find case studies suggesting it can; from Naomi Campbell showing off a fur Christmas gift after having fronted PETA’s ‘rather go naked than wear fur’ campaign[6], or Scarlett Johansson being forced to quit her ambassador role with Oxfam over her decision to appear in an advertising campaign for SodaStream, who own a factory in an Israeli settlement in the West Bank[7]. In both of these instances, the endorsements not only damaged the credibility of the star but also the integrity of their partner charity also.

One could contend that celebrity advocacy still converts many new supporters to the cause, and this far outweighs the dubious motivations of a minority. But even this utilitarian argument has fallen under scrutiny. Can we really credit celebrity influence with having secured swathes of new supporters? A survey commissioned by Third Sector suggests otherwise, with 69% of respondents neither more nor less likely to donate to a charity if a celebrity backed it, with a further 13% less likely to give.[8] Similarly, a study in the International Journal of Cultural Studies- drawing on two large surveys and a focus group- found that the public were far more likely to choose to support a charity “due to personal or family connections rather than celebrity-led promotion.”[9] With both industry and academic research seemingly undermining the value of celeb/charity partnerships, is it time to call the curtain on celebrity endorsements?

From our moral standpoint in the third sector, it’s already pretty easy to look-down on ‘self-obsessed’ celebrity culture and celebrities, with recent coverage and research making it even easier to be cynical at their attempts to engage with charitable causes. There is reason to be sceptical of general public surveys which rely on self-reporting of donation trends, particularly regarding motivation - are many people likely to admit a celebrity persuaded them to donate their hard-earned cash to a charity, and not the righteousness of the cause?

But the truth is that what motivates someone to support, for example, one animal charity over another are far more complex than is being assumed. Certainly, a potential donor will most likely have a personal or sentimental affinity with the cause. However, while a celebrity endorsement may not have been the key driver in the decision-making process, it is entirely plausible that a mention in a TV-interview, post on social media or quote in a newspaper drew attention to the charity in the first place (even if on a subconscious level).

In this sense, celebrities can help charities of all sizes secure media traction and audience access that would otherwise be out of reach. In her response to coverage of Brockington and Henson’s report, Rachel Braier (PR & Celebrity Manager for Haven House Children’s Hospice), notes that Third Sector illustrated the article with an image of two TOWIE personalities endorsing a fundraising event at her charity. She points out that, of all the billions of celebrity images available, they chose one promoting a local children’s hospice in suburban Essex, proving (somewhat ironically) that celebrity endorsement “really is a brilliantly cost-effective way of gaining brand awareness and cut-through.”[10]

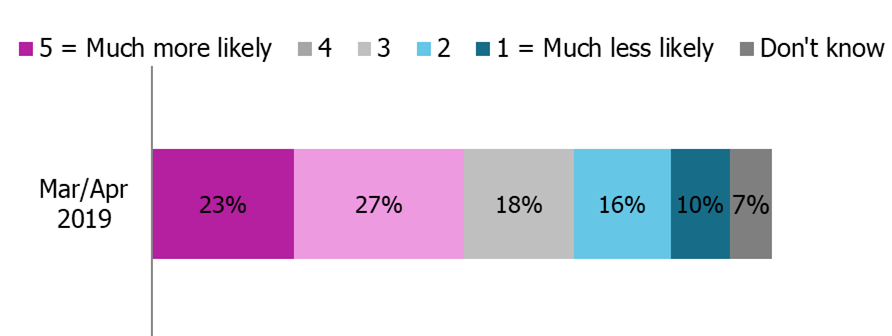

The fact is, despite recent criticism, journalists are more likely to cover a campaign if celebrities are used. Considering the popular attention and mainstream appeal stars bring, it is hardly surprising. Our bi-yearly research with journalists – the Journalists’ Attitudes and Awareness Monitor - shows that 50% of journalists surveyed were much more or more likely to cover an appeal if a celebrity was used.

“Does the use of celebrities in fundraising appeals make you more or less likely to cover the appeal, and why?”

It may not sit well with some, but celebrity involvement in a campaign is still likely to draw media attention to the charity and raise awareness of the cause with - directly or indirectly - donations and supporters following. Clearly Comic Relief had good reason to curtail the number of celebrity appearances this year[11] - but is it a coincidence that viewing figures dropped by 600,000 and donations by £8mn?[12] While surveys of the public may not identify celebrity endorsement as a driving factor behind donations, they do appear to have an impact.

This does not suggest that the motivations of individual celebrities are not still important, or that they cannot be detrimental to the cause they advocate for. It simply means that to maximise the value of celebrity endorsements, like any other fundraising practice, it must be done well. The personalities driving the campaign should have a knowledge and a real empathy for the cause, their values should reflect the long-term aims of the charity. Many charities already have strict standards for selecting famous partners, as Rachel Braier explains:

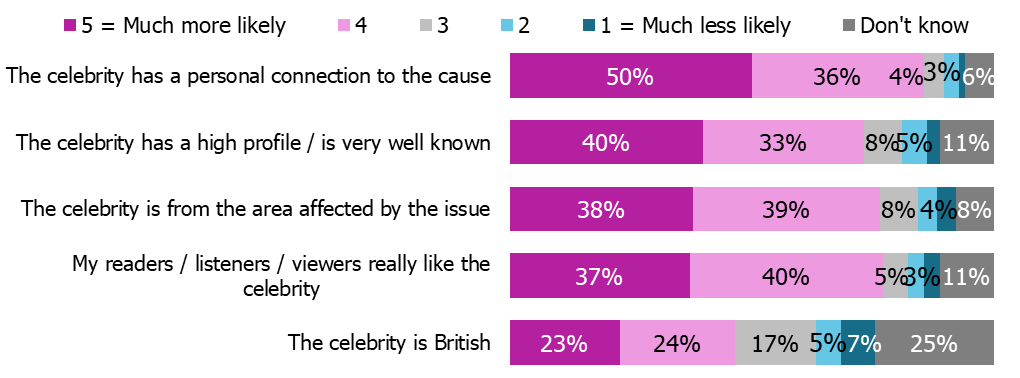

Nor are these conditions limited to charities - journalists also apply similar criteria when covering charity campaigns. Our research shows that the vast majority of journalists – 86%- were much more or more likely to cover a fundraising appeal if the celebrity had a personal connection to the cause - a factor influential above even the profile of the celebrity themselves.

“Would any of the following factors about a celebrity make you more or less likely to cover a fundraising appeal, in which the celebrity appears?”

It is not a case of all celebrity endorsements being advantageous or antithetical to charities, much less ‘good’ or ‘bad’ in themselves. The level of coverage the appeal receives and effectiveness of the partnership depends on circumstance, context and character. As one of our survey respondents from the BBC testified, “The right celebrity could help generate more coverage for a charity, if they had a genuine connection with the cause and it didn't appear too cynical.”

Just as one can easily recall examples of celebrity endorsements gone wrong, there are also instances where celebrities have campaigned for a cause with clarity and candour. Sir Ian McKellan (Stonewall) and Dame Joanna Lumley (Gurkhas’ rights) both provide excellent and widely-covered case studies of established personalities with strong personal connections to the appeals they advocated for.

Indeed, in a world where news is disseminated exponentially and consumed selectively on social media, tapping into the potential outreach of celebrities has never been more important. Take Anne Hegerty, for instance. A TV quiz show mastermind on “The Chase”, Anne’s openness in discussing her struggle after being diagnosed as autistic at 45 on “I’m a Celebrity” gained widespread coverage for the condition[13] and National Autistic Society[14], both in traditional and new media channels. Google searches for ‘autism’ hit a year-wide high in the UK[15], while National Autistic Society’s website crashed from increased traffic and calls to their helpline skyrocketed by 70%[16].

We live in an age where the line between celebrity and normality is blurred. Otherwise regular people command social media followings in the millions, and corporates readily harness their influence to maximise profit. With the third sector struggling to appeal to younger people as it is, why would charities deprive themselves of such a ready route to new audiences and fundraising streams? The cynics may moan that “celebrity culture is anti-culture; and it is sadly the dominant culture.” But as long as disproportionate media coverage (and influence) is apportioned to some individuals, their endorsements will be sought, for commercial and, yes, charitable purposes. If done effectively, this sad state of affairs can still benefit the third sector for years to come.

Our next wave of research with journalists starts very soon. If you’re interested in evaluating your charities’ media strategy, download a briefing pack (below), email JAAM@nfpsynergy.net, or give us a call on 020 7426 8888.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/feb/28/white-saviours-stacey-dooley-comic-relief-celebrities

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/02/angelina-jolie-celebrity-endorsement-curse-good-causes

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/02/angelina-jolie-celebrity-endorsement-curse-good-causes

[6] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/celebritynews/11309725/Former-PETA-campaigner-Naomi-Campbell-sparks-fury-over-fur-Christmas-gift.html

[7] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/scarlet-johansson-has-no-regrets-quitting-oxfam-for-sodastream-ad-campaign-9195715.html

[8] https://www.thirdsector.co.uk/people-say-celebrity-endorsement-does-not-affect-donation-decisions/fundraising/article/1459568

[10] https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/rachel-braier/famously-charitable-why-c_b_5674969.html?guccounter=1