In this week's blog, Research Assistant Tapinder explores the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on voluntary organisations supporting people from minority ethnic groups. Tapinder also shares how research and nfpSynergy can play a part in bridging the gaps between charities and audiences from ethnically diverse backgrounds.

Our world has been dominated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Not only are individuals from minority ethnic groups disproportionately affected by Covid, but voluntary organisations run by and for people from minority ethnic groups are also more likely to be negatively impacted. At the start of the pandemic, 9 out of 10 of these organisations become at risk of closing within just the first three months[1]. Third sector organisations supporting minority ethnic communities have been underfunded at a disproportionate rate, leaving them particularly disadvantaged in the face of Covid.

"Racism affects who works in the charity sector, who gets funding, what issues are prioritised, how strategies are developed and who is prioritised to receive help."

Charity So White – Defining Racism

A high-profile example of this impact is evidenced in Sistah Space's battle for a safe location in the London Borough of Hackney. Sistah Space, founded by Ngozi Fulani, is a small grassroots non-profit, supporting women of African and Caribbean heritage affected by domestic violence. Since their doors opened in 2014, they have filled significant gaps as the only service provision of its kind in London, helping Black women experiencing abuse. During the pandemic, Sistah Space have seen a 500% increase in calls for their specialist support. Yet, they found themselves fighting to continue this service after being evicted by the council, who failed to provide a safe location for their life-saving work to take place. Thankfully, through their tireless campaigning, generosity of supporters, and being brought to the forefront by prominent figures in the media, (even featuring in British Vogue), they have – only just – managed to remain open during this turbulent time. Meanwhile, there are other grassroots non-profits safeguarding minority ethnic women, like Hull Sisters, who are encountering all too similar challenges.

Campaigns such as Charity So White carry out work against institutional racism in the charity sector, highlighting the disproportionate impact of Covid on minority ethnic communities and grassroots organisations much like Sistah Space and Hull Sisters. They also focus on amplifying the voices of workers and service users of colour in the wider charity sector. Neglecting to acknowledge and understand the differing experiences of people from various ethnic backgrounds could be detrimental to the operation of non-profits and cause key groups of their existing or potential staff, volunteers, supporters, and beneficiaries to be overlooked. To me, it has never been more apparent that charities should recognize the experiences of individuals from different minority ethnic backgrounds and how these audiences engage with, identify with, and perceive the sector. Yet, there seems to be a glaring gap in research around this.

In 2019, nfpSynergy began its work with under-researched audiences and we have published free reports with the findings (which you can download here). We have already found significant differences between under-researched audiences and the rest of the general population when it comes to engagement with charities.

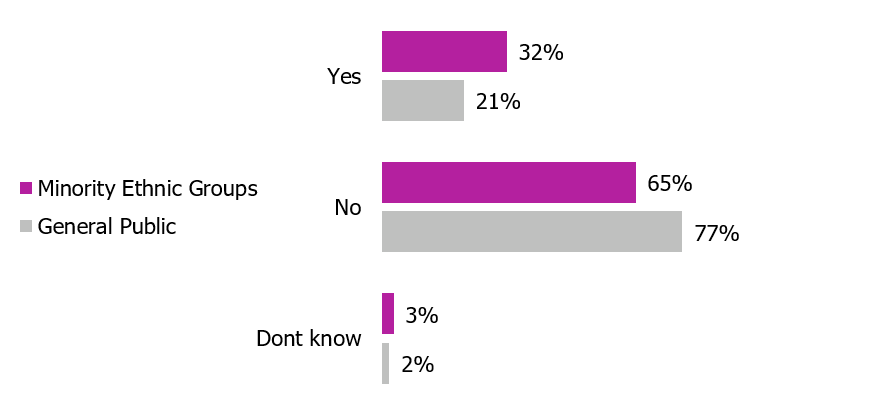

For example, in our November 2019 - January 2020 research, individuals we surveyed from minority ethnic groups were found 11% more likely to have volunteered in the past three months than the rest of the general public. To that end, the nation has seen individuals from minority ethnicities at the heart of the Covid-19 response, amongst those risking their health to help on the frontlines.

Volunteering behaviour (last 3 months)

“Have you given time as a volunteer in the last three months, to a charity or other organisation, or in your local community?”

Nov 2019 – Jan 2020, nfpSynergy | Base: 1,019 adults 16+, Britain; Charity Awareness Monitor, Oct 19, nfpSynergy | Base: 1,000 adults 16+, Britain

I strongly encourage charities and non-profits to actively become conversant with the struggles faced by marginalised communities and voluntary organisations that are run by and exist to support people from minority ethnic groups. Charities, however small or large, should also consider these often-overlooked audiences in their own work. We hope our research with minority ethnic audiences will assist participating non-profits in beginning to do this. We are repeating this research in March and any charity is welcome to get involved.

To find out more about our upcoming charity engagement research with people from minority ethnicities in the UK please contact secil.muderrisoglu@nfpsynergy.net.

As a company, we are aiming to move away from using the term BAME. The connotations and limitations of the term, which groups together and often generalises distinct minority ethnic groups, are becoming widely recognised[1]. In our next wave of research, we will also be asking participants what terms they identify with the most to help inform this change. If you have any thoughts, ideas, or suggestions around this please comment below.

nfpSynergy Twitter: @nfpSynergy

Sistah Space Twitter: @Sistah_Space

Hull Sisters Twitter: @Hullsisters

Charity So White Twitter: @CharitySoWhite

[1] Advance HE. Use of language: race and ethnicity. Guidance on approaching terminology around race and ethnicity. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/guidance/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/using-data-and-evidence/use-of-language-race-ethnicity

gal-dem. Bookmark this: the BAME acronym is often reductive and lazy.

https://gal-dem.com/bookmark-this-are-acronyms-like-bame-a-nonsense/

[1] Ubele Initiative. 2020. Impact of Covid-19 on the BAME community and voluntary sector. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/58f9e592440243412051314a/t/5eaab6e972a49d5a320cf3af/1588246258540/REPORT+Impact+of+COVID-19+on+the+BAME+Community+and+voluntary+sector%2C+30+April+2020.pdf

Independent. 2020. If lockdown continues, nine out of 10 BAME voluntary organisations will close. Who will support us then?

https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/coronavirus-lockdown-bame-charity-funding-racism-a9501921.html

Thank you for speaking truth

Thank you for speaking truth to power through extensive research and accessible data. I for one, totally eschew the term BAME because the issues that affect Black people do so in at a higher rate of disproportionality than any other ethnic group.

Simply recognising Black people as just that, beyond the homogeneity of BAME will highlight this fact, and perhaps highlight the institutionally and systemic racist biases that are endemic within British society.

Perhaps then, we can trully affect change for the positive.